Reflections on a Summer Retreat

“Hello sun in my face

Hello you who wake the morning

And spread it over the fields

And into the faces of tulips

And the nodding morning glories

And into the windows of, even, the

Miserable and the crotchety –

Best preacher that ever was

Dear star, that just happens

To be where you are in the universe

To keep us from ever darkness

To ease us with its warm touching

To hold us in the great hands of light

Good morning, Good morning, Good morning

Watch now how I start the day

In happiness, in kindness”

Before the sun, a new moon rises - a slender crescent against a dark sky - and my heart lifts. I wake my beloved sister and we walk silently towards the still-dark quiet of the Sardinian sea. Before we reach the deserted beach, the promise of dawn shows itself mauve and lavender in hue. From the path’s edge, a faint scent of wild fennel spills as we pass by, and cockerels, distant in the hills, call and respond to the coming of a greater light.

At my favourite spot - the end of a board-walk that later in the day will lead soft-footed bathers towards the water across the unforgiving pebbles of the beach - an elderly bespectacled widow dressed all in black - hair covered in the traditional way - rests on the stability of an over-turned boat. Very still, silent and alone, she waits here each day and watches patiently until the crimson orb of the sun suddenly shimmers into view, disrupting the perfect line of the sea’s horizon with fiery, morning glory.

My sister and I free our selves of clothes and wade happily into the surprising warmth and darkness of mercurial waters; I feel the old woman’s eyes on us, but sense no disapproval, and imagine that she enjoys our freedom of spirit and movement. Together, we swim towards the horizon until the pull of sun and moon begins to move the water and stir the waves from their slumber. Easily, my sister stretches out to float, her ears submerged, and I know that before any other human disturbance, she is listening to the sound of the sea - alive, all alive, all around.

Before long, as the sun quickly establishes its taken for granted presence in the sky, we are moved to return to shore, and see that the elderly woman has already started her return journey. Bent over, leaning on her stick, she makes her way along the board-walk toward the beautiful pine trees lining the beach, and beyond those, to the dusty road. I wonder about her story, and feel sure that, like us, she has consoled herself, and found joy in the awe and wonder of celestial bodies rising on our planet.

Saluting the Sun

Here, in the Ogliastra Province of south-east Sardinia, as in Ikaria, in Greece; Nicoya Province, in Costa Rica; Loma Linda in California and in Okinawa in Japan, anthropologists have discovered that humans are most likely to be living in alignment with the conditions for human flourishing. As a result, elders in these regions enjoy the longest, healthiest and most vital lives of all humans on the planet. In these locations, called Blue Zones, older people are free of the degenerative diseases of mind and body that plague modern western life and they reach a ripe old age.

Remarkable about all these places, despite their geographical, social and cultural diversity, is that exceptional health and longevity is the outcome of the same nine variables for the organisation of human existence. One of these variables is the regular experience of awe and wonder in the face of being in the world - a sense (not necessarily religious) of existing in relation to the beauty of nature and the magnificence of the universe. The elderly widow on the beach at dawn each day in Sardinia is the living embodiment of the value to human health and happiness of acts of simple veneration. Existing close to the elements, in touch with cultivation of the earth and sea, and dwelling under star-filled heavens, older people in the five Blue Zones of the world live a good life. They have spent their years engaged in meaningful labour, not necessarily well paid, doing tasks that might be quite physically demanding, but Blue Zone residents certainly don’t work too hard. With their relatively laid-back approach to life, they teach us that stress and over-work without adequate rest is the enemy of vitality. People growing old and staying healthy in the Blue Zones eat good food grown in good soil, (mostly vegetable, pulse, nut and grain, but not a vegetarian diet) and they drink a little wine each day in the enjoyment of good company.

Most interesting of all is that none of the elders in these communities have devoted hours of their lives to exercise, or yoga classes in an effort to stay fit and healthy. Rather, they have lived lives in which, moving naturally through the everyday activities of walking, gardening, fishing, labouring, swimming, dancing etc, they will have, in the most taken-for-granted, un-self-conscious way, regularly exercised the joints and muscles of the body through their full range of motion. Surrounded by family and friends in close-knit communities, where elders are highly respected and placed at the centre of family life, older people in the Blue Zones enjoy the loving company of younger generations and thrive. In the mountain villages of Sardinia, for example, there are the world’s highest number of centenarians, and beautiful street murals celebrate the world-famous status of village elders.

Why then, if yoga is not part of the culture of Blue Zone living, do I propose the practice of yoga as part of a Blue Zone retreat at the beautiful Galanias centre in Ogliastra? The proposition, because the majority of us are removed, for the most part, from the habits of life that are conducive to well-being, is to introduce yoga as an alternative to the activities provided by natural movement and simple living that are so essential to human well being. On retreat, the opportunity also arises to drop into a slower pace of life, to enjoy the warm-hearted, joyful company of new friends, and old acquaintances, and to experience a supportive community of yoga practice in a beautiful natural environment. Swimming in the sea, eating local food, and drinking local wine, we try out new rituals of self-care including the sensual medicine of Doterra essential oils and together, we experiment with what it feels like to carefully engage with the enquiry that yoga offers. Through safe exploration of a set of practical movement and breath techniques, tried and tested over centuries, it becomes clear that it is possible, even in just one week, to address and begin to remove the obstacles that stand in the way of a life lived in alignment with the flow of energetic vitality.

“Yoga is a technology for removing the illusory veil that stands between us and the animating force of life.”

This understanding of what yoga offers – the chance to ‘come back to life’ – brings a whole new meaning to the alignment-based method of yoga that I have learned to teach. The practice of seated meditation, restorative spinal release in the evening, and, strength building sun salutation sequences in the morning, offer more than the potential to gain insight, or to bring muscles and bones into alignment, slowly bringing integrity, suppleness and strength to the muscular-skeletal form: these practices also make it possible to cultivate everyday, a gentle background appreciation of what it means for us to exist on a planet filled with life, in a solar system where, remarkably, humans can harness and circulate energy in and through the physical form. This is why, like the elderly Sardinian widow on the beach at dawn, we take time to rise early and salute the sun. We come back to the yoga mat each morning to quietly remind ourselves of the source of light and life on earth and each time we see the sun rise, it lifts our hearts: even if only for a moment, our spirits soar…

“The sunrise ... was a phenomenon that overwhelmed me anew every day. The drama of it lay less in the splendour of the sun’s shooting up over the horizon than in what happened afterward. I formed the habit of taking my camp stool and sitting under an umbrella acacia just before dawn. Before me, at the bottom of the little valley, lay a dark, almost black-green strip of jungle, with the rim of the plateau on the opposite side of the valley towering above it. At first, the contrasts between light and darkness would be extremely sharp. Then objects would assume contour and emerge into the light which seemed to fill the valley with a compact brightness. The horizon above became radiantly white. Gradually the swelling light seemed to penetrate into the very structure of objects, which became illuminated from within until at last they shone translucently, like bits of coloured glass. Everything turned to flaming crystal. The cry of the bell bird rang around the horizon. At such moments I felt as it I were inside a temple. It was the most sacred hour of the day. I drank in this glory with insatiable delight, or rather, in a timeless ecstasy. ”

Cultivating Presence

Energised by a dawn swim, deeply comforted by my sister’s company, and inspired by the dedication of the elderly woman whose day begins with such a quiet and simple, but spectacular act of devotion, it is not difficult for me, and my beloved daughter, Omotayo (who lends her beautiful presence to the work of assisting me on retreat), to encourage others on yoga holiday with us in Sardinia to rise early and come together to salute the sun.

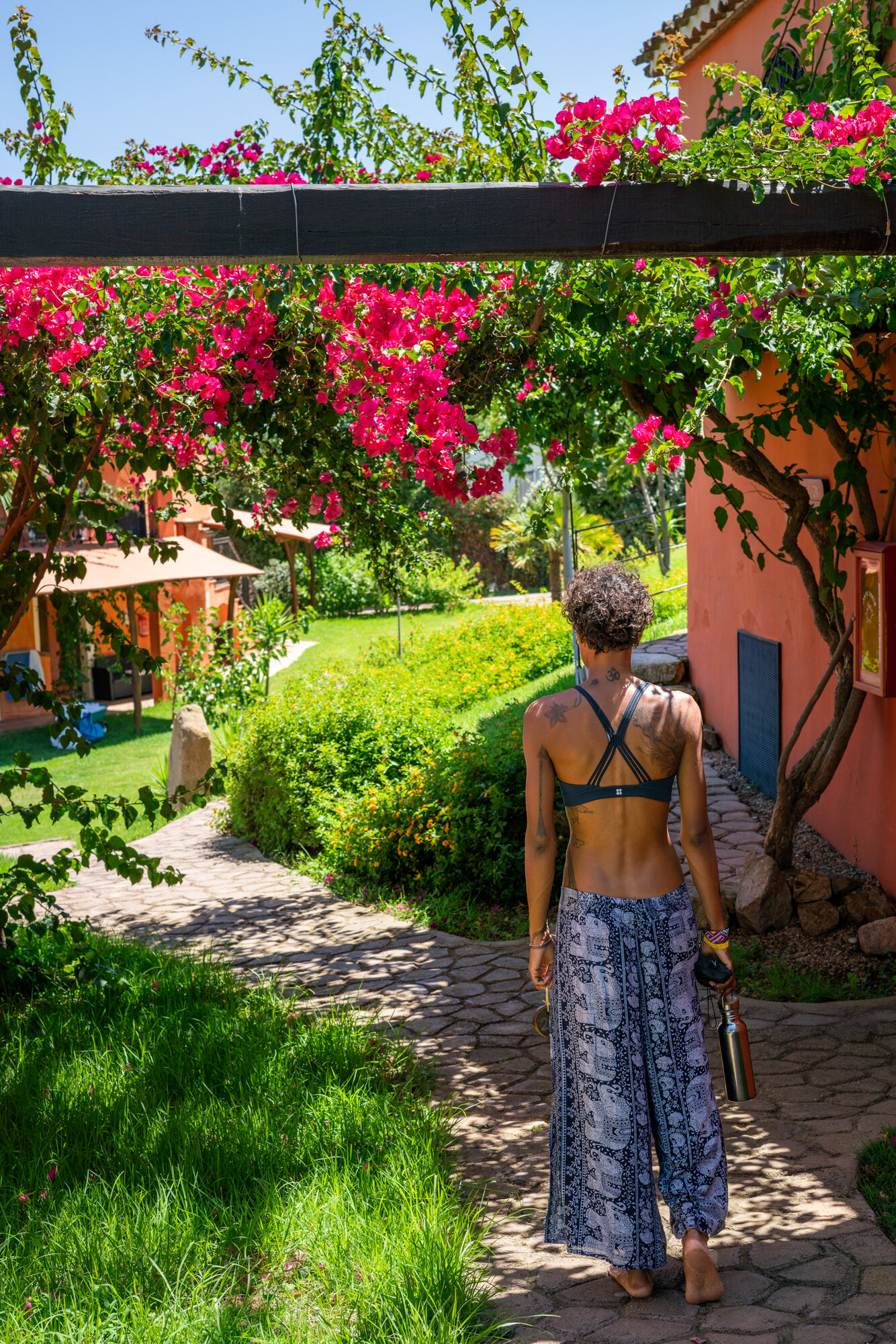

Surrounded by all the elements – sun, sea, sky and land - it is easier for us to persuade people to drag themselves out of bed to join the enquiry of a morning yoga practice. Sleepily, and more, or less grumpily, guests make their way among our striking, terracotta- orange dwellings and through the peace and quiet of flower-filled gardens; traipsing slowly up hill, they straggle in twos, threes and solitary ones, and I imagine they are slowly seduced to wakefulness, gaining encouragement each day from the stunning sight of a Sardinian sunrise.

Softly, a warm breeze blows through the beautiful open-air yoga shala, and gradually, guests are persuaded by the idea that the effort is worthwhile of reaching our vantage point overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. I know it is not easy to arrive to a morning yoga practice through the invitation of a seated morning meditation. This is often the most challenging part of a retreat – the invitation to be still, and, sitting in stillness, to explore what it might mean to sit well with one’s self. If only the focus of the retreat was simply the execution of difficult physical postures, that would be easier. Wouldn’t it be so welcome - the constant challenge of movement, the distraction of gymnastic instructions and the possibility to rush headlong, towards a sense of achievement? Instead, the idea is that in a comfortable seated position, with a growing awareness of the rise and fall of the breath - and resting in the steadiness of that tidal motion - we can find sufficient courage to tune into and pay attention to the inner landscape.

This, as I understand it, is part of the objective of yoga - to learn how to listen to the body - to practice the art of discernment, exploring what kind of knowledge is to be discovered by gazing inwards. How, for example, does the breath move the form of the body? What is the feeling of the physical form of the body on any particular morning? Is the mind easy to settle in the breath, or does it run away with itself like a crazy horse as the mind is want to do? What is the quality of energy, or vitality – is it full and freely moving - or is there a sense of tightness, weakness, or contraction in the subtle body? How do emotions take up residence and inhabit the body, creating sudden upward surges of joy, at sunrise for example, or coalescing in long-held angers, or fears that create holding patterns in the form? The answers to these questions enable us to use the body in meditation as a finely balanced barometer, posing anew the same questions each day, and cultivating curiosity about the different answers that arise from the constant flux of existence, and the repeated act of gazing inwards.

How am I in my self? What does the experience of being in the body have to reveal about what life is really, truly like at the moment? Is it possible for me to breathe alongside whatever truths arise, no matter how difficult, instead of trying to escape the difficult, and, sometimes, unbearable feeling of being alive? And, what clues does the body give about what might be needed to bring life back into balance when we are thrown off centre? If only we can learn to be perceptive to this form of in-sight, meditation can become a subtle, but powerful tool for personal transformation. Its promise, which I understand to be one of the primary aims of the practice of yoga, is an expanding state of awareness. Arising out of this awareness, the opportunity emerges on a daily basis to recalibrate, to re-approach and to re-discover one’s self and to feel from within what is needed to re-centre, and experience, even if only for a few minutes each day, a blissful state of relaxed and natural equilibrium.

The invitation, towards the end of the mediation, which takes no more 20 minutes, is to gently open the eyes and, with the same quality of attention, to take a moment to notice the quality of the morning’s light; the sounds of the world coming to life all around; the feel and temperature of the air on the skin; the textures of the surface of the world; the smell of the air entering the nostrils with the breath and the taste in one’s mouth. Cultivating equanimity between the awareness and appreciation of both inner and outer landscapes, a fullness of appreciation arises for the beautiful complexity of existence. Wonderful about this simple act of practising whole perception is that it can change the tenor of the unfolding day, leading to a softening and opening of the heart and a strengthening of courage, providing something to rest against when life is endlessly challenging. It renews, on a daily basis, the chance to start again, and to try once more to take responsibility for the presence one brings to the world and to other people in it. The secret, whether you an elderly Sardinian widow, or a student on yoga retreat, is to wake up to the dawning of the day, and through the day and its beauty, to the awakening of one’s self. I call this a practice of Cultivating Presence, which I first learned on retreat in Turkey with my wonderful teacher, Anna Ashby who encourages students to think of meditation in yoga as the art of truly paying attention. For me, this brings to mind, and I share on the first morning of our retreat, a quote from Mary Oliver’s beautiful contemplation - Upstream - on the inseparability of human life from the natural world:

“In the beginning I was so young and such a stranger to myself I hardly existed. I had to go out into the world and see it and hear it and react to it, before I knew at all who I was, what I was, what I wanted to be. Wordsworth studied himself and found the subject astonishing. Actually what he studied was his relationship to the harmonies and also the discords of the natural world. That’s what created the excitement.

I walk all day across the heaven-verging field.

And whoever thinks these are worthy, breathy words I am writing is kind. Writing is neither vibrant life nor docile artefact but a text that would put all its money in the hope of suggestion. Come with me into the field of sunflowers is a better line that you will find here, and the sunflowers themselves far more wonderful that any words about them.

I walked, all one spring day, upstream, sometimes in the midst of ripples, sometimes along the shore. My company were violets, Dutchman’s-breeches, spring beauties, trilliums, bloodroot, ferns rising so curled one could feel the upward push of delicate hairs upon their bodies. My parents were downstream, not far away, then farther away because I was walking the wrong way, upstream instead of downstream. Finally I was advertised on the hotline of help, and yet there I was, slopping along happily in the stream’s coolness. So maybe it was the right way after all. If this was lost, let us all be lost always. The beech leaves were just slipping their copper coats; pale green and quivering they arrived into the year. My heart opened again and again. The water pushed against my effort, then its glassy permission to step ahead touched my ankles. The sense of going toward the source.

I do not think I ever returned home.

Do you think there is anything that is not attached by its unbreakable cord to everything else? Plant your peas and your corn in the field when the moon is full, or risk failure. This has been understood since planting began. The attention of the seed to the draw of the moon is, I suppose measurable, like the tilt of the planet. Or, maybe not – maybe you have to add some immeasurable ingredient made of the hour, the singular field, the hand of the sower.

It lives in my imagination strongly that the black oak is pleased to be a black oak. I mean all of them, but in particular one tree that leads me in Blackwater, that is as shapely as a flower, that I have often hugged and put my lips to. Maybe it is a hundred years old. And who knows what it dreamed of in the first springs of its life, escaping the cottontail’s teeth and everything dangerous else. Who knows when supreme patience took hold, and the wind’s wandering among its leaves was enough of motion, of travel.

Little by little I waded from the region of coltsfoot to the spring beauties. From there to the trilliums. From there to the bloodroot. Then the dark ferns. Then the wild music of the waterthrush.

When the chesty, fierce-furred bear become sick he travels the mountainsides and the fields, searching for certain grasses, flowers, leaves and herbs that hold within themselves the power of healing. He eats, he grows stronger. Could you, oh clever one, do this? Do you know anything about where you live, what it offers? Have you ever said, ‘Sir Bear, teach me. I am a customer of death coming, and would give you a pot of honey and my house on the western hills to know what you know.’

After the water thrush there was only silence.

Understand from this certainty. Butterflies don’t write books, neither do lilies or violets. Which doesn’t mean they don’t know, in their own way, what they are. That they don’t know they are alive – that they don’t feel that action upon which all consciousness sits, lightly or heavily. Humility is the prize of the leaf-world. Vain-glory is the bane of us, the humans.

Sometimes the desire to be lost again, as long ago, comes over me like a vapour. With growth into adulthood, responsibilities claimed me, so many heavy coats. I didn’t choose them, I don’t fault them, but it took time to reject them. Now, in the spring, I kneel, I put my face into the packets of violets, the dampness, the freshness, the sense of ever-ness. Something is wrong, I know it, if I don’t keep my attention on eternity. May I be the tiniest nail in the house of the universe, tiny but useful. May I stay forever in the stream. May I look down upon the wind-flower and the bull thistle and the coreopsis with the greatest respect.

Teach the children. We don’t matter so much, but the children do. Show them the daisies and the pale hepatica. Teach them the taste of sassafras and wintergreen. The lives of the blue sailors, mallow, sunbursts, the moccasin flowers. And the frisky ones – inkberry, lamb’s-quarters, blueberries. And the aromatic ones – rosemary, oregano. Give them peppermint to put in their pockets as they go to school. Give them the fields and the woods and the possibility of a world salvaged from the lords of profit. Stand them in the stream, head them upstream, rejoice as they learn to live this green space they live in, its sticks and leaves and then the silent, beautiful blossoms.

Attention is the beginning of devotion.”

We work slowly on our Sardinian retreat towards the expression of a beautiful yoga pose called Camatkarasana, which might be translated from Sanskrit into English as the ecstatic opening of the enraptured heart. We do this not because it is an impressive pose as it unfolds, but rather because it provides the opportunity to express in physical form what we are experiencing as the consequence of being in nature - the lifting and opening of the heart and the reward of this - the rare sensation of rapture - the soaring of the spirits. The idea is that joyful as our human company may be, there is solace to be sought in nature and a steadiness in grounding our attention and energy in the earth that can become the foundation of our lives, especially when all else fails us. On the mat, we prepare carefully over the course of a week, and practice stabilising and strengthening the foundations of the pose before we initiate the action of lifting, and opening, rising out of the ground - exploring, trusting - reaching, soaring…

Mary Oliver leads us to Walk Whitman and I am thrilled. In Leaves of Grass Whitman ‘sings the body electric’ and explains what it means to truly pay attention to the joy of human embodiment; he reveals through poetic observation the grace and poise of natural movement and the enchantment of humans in their taken-for-granted situations of cultural action. Whitman’s meditation on the vitality of the physical form in older age and what he brings to our attention, which is the joy and solace of human company, is both an apt tribute to the elders of the Blue Zones and a clarification of what an alignment-based yoga practice makes possible. Part of the reason for the everyday effort, the discipline of the practice, is to bring muscles and bones; breath and body; mind, breath and body; mind, breath, body and life force into alignment, so that we might ultimately experience greater ease being embodied as human. With the enjoyment of greater ease, we might then reap the rewards of what yoga promises, which is a lessening of our suffering. Hoping to lend encouragement to students of all ages by sharing the poignancy of Whitman’s words, I am moved again by his powers of discernment and deeply grateful on retreat for the gift of everyone’s heart-warming company. I read aloud:

“The expression of a well-made man appears not only in his face,

It is in his limbs and joints also... it is curiously in the joints of his hips and wrists,

It is in his walk... the carriage of his neck... the flex of his waist and knees... dress does not hide him,

The strong sweet supple quality he has strikes through the cotton and flannel;

To see him pass conveys as much as the best poem...

perhaps more,

You linger to see his back and the back of his neck and shoulderside.

The sprawl and fulness of babes... the bosoms and heads of women... the folds of their dress... their style as we pass in the street... the contour of their shape downwards;

The swimmer naked in the swimming bath... seen as he swims through the salt transparent greenshine,

or lies on his back and rolls silently with the heave of the water;

Farmers bare-armed framing a house... hoisting the beams in their places... or using the mallet and mortising chisel,

The bending forward and backward of rowers in rowboats... the horseman in his saddle;

Girls and mothers and housekeepers in all their exquisite offices,

The group of labourers seated an noontime with their open dinnerkettles, and their wives waiting,

The female soothing a child... the farmer’s daughter in the garden or cowyard,

The woodman rapidly swinging his axe in the woods... the young fellow hoeing the corn... the sleighdriver guiding his horses through the crowd,

The wrestle of wrestlers... two apprentice-boys, quite grown, lusty, goodnatured, nativeborn, out on the vacant lot at sundown after work,

The coats vests and caps thrown down... the embrace of love and resistance,

The upperhold and underhold - the hair rumpled over and blinding the eyes;

The march of firemen in their own costumes - the play of the masculine muscle through cleansetting trowsers and waistbands,

The slow return from the fire... the pause when the bell strikes suddenly again - the listening on the alert,

The natural perfect and varies attitudes... the bent head, the curved neck, the counting;

Such life I love... I loosen myself and pass freely...

and am at the mother’s breast with the little child,

And swim with the swimmer, and wrestle with wrestlers, and march in line with the firemen, and pause and listen and count.

I knew a man ... he was a common farmer... he was the father of five sons... and in them were the fathers of sons... and in them were the fathers of sons.

This was a man of wonderful vigor and calmness and beauty of person;

The shape of his head, the richness and breadth of his manners, the pale yellow and white of his hair and beard, the immeasurable meaning of his black eyes,

These I used to go and visit him to see... He was wise also,

He was six feet tall... he was over eighty years old... his sons were massive clean bearded tanfaced and handsome,

They and his daughters loved him... all who saw him loved him.. they did not love him by allowance... they loved him with personal love;

He drank water only... the blood showed like scarlet through the clear brown skin of his face;

He was a frequent gunner and fisher... he sailed his boat himself... he had a fine one presented to him by a shipjoiner... he had fowling pieces, presented to him by men that loved him;

When he went with his five sons and many grandsons to hunt or fish you would pick him out as the most beautiful and vigorous of the gang,

You would wish long and long to be with him... you would wish to sit by him in the boat that you and he might touch each other.

I have perceived that to be with those I like is enough,

To stop in company with the rest at evening is enough,

To be surrounded by beautiful curious breathing laughing flesh is enough,

To pass among them... to touch any one... to rest my arm every so lightly round his or her neck for a moment... what is this then?

I do not ask any more delight... I swim in it as in a sea.”

In the beautiful portraits below, the brilliant retreat photographer – Stanislav Grapatin – sensitively reveals something of the atmosphere of our summer retreat in Sardinia at the Galanias retreat centre. All images are copyright protected, so please ask for permission if you want to use any of these photographs.

If you are interested in joining the summer retreat of 2020, find out more about the offer of a week, or two weeks in the Blue Zone of Costa Rica, email Gillian - yogianthropologist@gmail.com - more details to follow soon.

If you are interested in joining the Winter Retreat, - Yoga and Hiking in Yorkshire - register your interest by email. Save the date: 2nd - 6th January 2020 and find out more here.